Vashti Comes to America

Originally published in Esther in America, pps. 105-115.

Vashti, Ahasuerus’ first queen, is among the most enigmatic characters in the Book of Esther. While the king revels with his subjects for some six months, he commands Vashti to appear before him “to display her beauty to the peoples and the officials” (Est. 1:11). For unstated reasons, Vashti refuses to attend. The king, infuriated, consults with his advisors, one of whom recommends “that Vashti never [again] enter the presence of King Ahasuerus,” and that the king “bestow her royal status upon another who is more worthy than she” (1:19). This leads Ahasuerus to launch an international search for a new queen, setting the stage for the selection of the Jewess Esther and the remainder of the book’s narrative.

What are we to make of Vashti’s refusal? Is she a villainess who deserved her fate, heroic conscientious objector, or simply a literary nonentity who paves the way for Queen Esther’s rise? To set the stage for the reception of Vashti in the New World, it is worth beginning with an overview of classical Jewish and Christian readings of this cryptic character.

For the Jewish community, of course, the Book of Esther has played a central role for millennia. The story is traditionally viewed as a paradigmatic case of God’s hidden hand in history, and Esther and Mordecai are valorized as heroes. Vashti’s character, in contrast, has been interpreted in an overwhelmingly negative light. The Midrash identifies her as the granddaughter of Nebuchadnezzar, who had destroyed the First Temple,1 and credits her with convincing Ahasuerus to abrogate the Second Temple rebuilding project referenced in Ezra 4:6.2 In recompense for having brutally forced her Jewish servants to work naked on Shabbat, she is bidden to appear unclothed on the seventh day of the party.3 Hardly a pawn of the hedonic king, Vashti too seeks promiscuity – after all, the verses state explicitly that just like her husband, she had been holding a parallel party in the palace – and would have happily appeared naked (aside from her crown), which is precisely how the Rabbis imagine that she is bidden to appear.4 She refuses her husband’s request not out of modesty or principle but vanity, only because she grows a tail or contracts leprosy.5 As a result of her wickedness, while the text leaves her ultimate fate unclear, according to the Rabbis she is executed.6 Put simply, the rabbinic tradition depicts Vashti as a vile scoundrel, the wicked counterpart to the righteous Queen Esther.7

Unlike early rabbinic interpretation, however, the Book of Esther received relatively little attention in the Church.8 While Esther was incorporated into the New Testament, this inclusion was largely begrudging. It is no coincidence that the first Christian commentary on Esther, by Rabanus (Hrabanus) Maurus, did not appear until the ninth century.9 Martin Luther went so far as to write, “I am so hostile to this book [2 Maccabees] and Esther that I wish that they did not come to us at all, for they have too many heathen unnaturalities.”10 In 1837, The Reverend W. Niblock, Headmaster of London High School, offered a catalog of Christian concerns with Esther: “It contains no promise to the Church, makes no mention of the Gospel, has no type or prophecy of the Messiah, does not once introduce the name of God or recognize his providence, reveals none of ‘those precious and fundamental doctrines’ found elsewhere in the Old Testament and is not quoted in the New Testament.”11 Lewis Bayles Paton (1864–1932), an American biblical scholar, archaeologist, and historian, later asserted: “The book is so conspicuously lacking in religion that it should never have been included in the Canon of the OT, but should have been left with Judith and Tobit among the apocryphal writings.”12

Noting this long history of dismissal by Christian thinkers, the contemporary Christian scholar Frederic Bush, while advocating that Christians pay closer attention to the Book of Esther, acknowledges that he faces a steep uphill climb, titling one of his articles, “The Book of Esther: Opus non gratum (underappreciated work) in the Christian Tradition.”13

Christian neglect notwithstanding, the Middle Ages saw a resurgence of interest in the character of Esther herself, albeit not on a popular level. Christian medieval discussions14 focused on Esther as a model for contemporary queens. Additionally, Christian writers relied on the Greek version of the story, in which the name of God appears frequently, making it a more comfortable religious text on which to rely.15 Still, these recommendations for royals notwithstanding – it remains unclear whether any female sovereigns in fact utilized the book in this way – Esther remained a closed book for the masses.

Esther was finally popularized in Christian circles during the Puritan period, thanks to Cotton Mather’s classic Ornaments for the Daughters of Zion, a conduct manual in which Esther appears as one of the biblical heroines adduced as a model of proper behavior.16 For Mather, Esther was the ideal woman inasmuch as she supported her husband Ahasuerus even as she urged him to improve his character. Mather’s guide was highly influential and was widely read through the nineteenth century.17

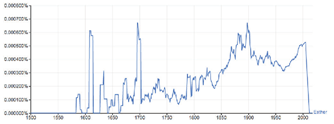

But even as Mather wrote extensively about Esther, he paid scant attention to Vashti. This usage differential remained the norm through much of the eighteenth century. Here is an n-gram graph, representing the percentage of total published books18 that include at least one usage of the word Esther over the last five hundred years:

And here is Vashti:

The contrast speaks volumes. Note the glaring absence of Vashti’s name in published books before the eighteenth century. Even afterward, a close reading of the graphs indicates the dramatic gap between usages of the two throughout. And so, as the close of the eighteenth century approached, while Esther was invoked by Mather, a highly popular and influential author, as a model wife, Vashti was effectively ignored.

As a result of this lacuna, as the first wave of feminists began to rise in the nineteenth century, Vashti still remained “unclaimed” in the Christian West. This vacuum created an opening for “a remarkable number of nineteenth-century women poets” and authors to begin turning to Vashti as a role model.19

As early as 1820, in her Judith, Esther and Other Poems, American poet Maria Gowen Brooks (1794–1845) offered a vigorous defense of Vashti’s refusal to appear before the king. It was amid this shifting environment that, in 1847, Great Britain’s Poet Laureate Lord Alfred Tennyson issued a paean to the deposed queen:

O Vashti, noble Vashti!

Summon’d out She kept her state,

and left the drunken king

To brawl at Shushan underneath the palms. (The Princess, Part 3)

While writing from the other side of the pond, Tennyson’s depiction of Vashti was to prove highly influential among leading American thinkers and activists.

The year 1857, just four years prior to the American Civil War, saw another key development, with outspoken abolitionist Frances Harper joining the ranks of fellow feminists in penning a poem simply titled “Vashti” – a title that would have been unheard of in the eighteenth century. Harper depicts Vashti’s defiant, emotional response to the king:

“Go back!” she cried, and waved her hand,

And grief was in her eye:

“Go, tell the King,” she sadly said,

“That I would rather die…”

She heard again the King’s command,

And left her high estate;

Strong in her earnest womanhood,

She calmly met her fate,

And left the palace of the King,

Proud of her spotless name –

A woman who could bend to grief,

But would not bow to shame.

Harper’s vivid depiction reflects the larger alliance between feminists and abolitionists in the nineteenth century. Both groups sought to rectify the immoral exclusion of a significant segment of society, and many were active in both feminist and anti-slavery circles.

In 1878, another famed abolitionist and feminist, Harriet Beecher Stowe, weighed in regarding Vashti’s fate:

Now, if we consider the abject condition of all men in that day before the king, we shall stand amazed that there was a woman found at the head of the Persian empire that dared to disobey the command even of a drunken monarch…. Vashti was reduced to the place where a woman deliberately chooses death before dishonor.20

For Harper and Beecher Stowe, Vashti became the great exemplar of the disenfranchised individual – woman, slave, or both – who refuses to consent to her master’s advances.21

Later, Anglo-American poet, lawyer and politician John Brayshaw Kaye named his 1984 poem “Vashti.” Kaye portrays Vashti as a wise and virtuous woman who finds herself exiled because of court politics; she adopts an orphan girl, Meta, and takes care of her, and lives out her life after the palace in solitude, but also close to nature and beauty, and loved by her adopted daughter. Such a description of Vashti would have been unthinkable some two hundred years prior. The integration of Vashti into non-polemical literature is perhaps the greatest testimony to the way in which she had deeply penetrated popular culture.

Perhaps most influential was Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s 1895 Women’s Bible. Comparing Vashti favorably with numerous female biblical heroines, Stanton declares:

We have some grand types of women presented for our admiration in the Bible. Deborah for her courage and military prowess; Huldah for her learning, prophetic insight and statesmanship, seated in the college in Jerusalem, where Josiah the king sent his cabinet ministers to consult her as to the policy of his government; Esther, who ruled as well as reigned, and Vashti, who scorned the Apostle’s command, “Wives, obey your husbands.” She refused the king’s orders to grace with her presence his revelling court. Tennyson pays this tribute to her virtue and dignity:

“Oh, Vashti! noble Vashti! Summoned forth, she kept her state, And left the drunken king to brawl In Shushan underneath his palms.”22

As Lucinda Chandler, fellow feminist and co-author of the The Women’s Bible with Cady Stanton, writes on the very next page: “Vashti is conspicuous as the first woman recorded whose self-respect and courage enabled her to act contrary to the will of her husband. She was the first woman who dared.”23 The Women’s Bible has been cited countless times in contemporary treatments of Vashti’s heroism.

Despite the initial congruity among feminists and Black activists, in time Vashti began to take on a life of her own in the Black community. For instance, “Vashti” became a relatively common first name that Blacks gave to their children. Perhaps the most prominent example is Vashti Murphy McKenzie (b. May 28, 1947), a bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and the first female elected bishop in the denomination’s history. Peter H. Reynolds’ 2003 classic children’s book The Dot24 follows a young lady named Vashti; Reynolds reports that he came up with her name after a chance encounter at a Massachusetts coffee house with a young lady named Vashti.25

Individuals named Vashti are also featured as major characters in numerous twentieth-century works of Black literature. To take just a few illustrative examples: In Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved, Vashti is the name of Stamp Paid’s wife. A woman named Vashti plays a prominent role in the theatrical production of “For Your Soul’s Sake – A Soul Opera” (2007); like her biblical namesake, she speaks about making independent, principled decisions, irrespective of how they will be received by others. The Black actress Butterfly McQueen portrays a servant girl named Vashti in the 1946 film Duel in the Sun. The simple fact that Vashti appears so prominently in twentieth-century Black literature suggests just how mainstream her name has become among members of that community.

There is even an organization named Vashti, whose mission statement reads in part: “VASHTI is a value-driven, faith-based communication and leadership enhancement initiative. VASHTI was conceived to strengthen the presence and voices of Black women and girls as progressive facilitators, teachers, trainers and advocates.”26

What can help to account for the unique staying power of Vashti in the Black community in particular? In his groundbreaking work on the relationship between fiction and jazz music, The Hero and the Blues, Black literary critic Albert Murray (1916–2013) explains: “What must be remembered is that people live in terms of images which represent the fundamental conceptions embodied in their rituals and myths. In the absence of adequate images they live in terms of such compelling images (and hence rituals and myths) as are abroad at the time.”27 Blacks before and after emancipation often turned to the Bible for personal examples as to how to ensure freedom and live a whole and meaningful life. As Anthony Pinn, a contemporary Black theologian, has contended, Black religion can be seen as “the quest for complex subjectivity, a desire or feeling for more life meaning. In other words, black religion’s basic structure entails a push or desire for fullness.”28 This desire to not just revere but to embody their role models gave Vashti a far more interpretively integrated role in the Black community.

With the passage of the 19th amendment in 1920 granting women the right to vote, the Vashti rhetoric settled down. But, owing to her already extensive interpretive history, Vashti rose once again to feminist fame in the 1980s. It was “during that decade that Alice Laffey, an expert on women in the Old Testament, noted that it was not surprising that Vashti appealed to modern feminists more than Esther did, as ‘buried in Esther’s character is also full compliance with the patriarchy.’”29 As Laffey put it succinctly, “Vashti never speaks yet her actions speak loud and clear: NO! She will not become the sexual object of drunken men!”30 Similarly, Valerie Freireich’s 1996 short story “Vashti and God” explores the queen’s inner world in great depth, even imagining that Vashti had a hand in assisting Esther’s transition to the throne. And, moving into the new millenium, in Vashti’s Victory and Other Biblical Women Resisting Injustice,31 Reverend Laverne McCain Gill presents Vashti as the paragon of anti-patriarchal resistance, in whose footsteps other biblical women walked.

Given the embrace Vashti has received on American shores over the past two hundred years, it comes as no surprise that as the #MeToo movement began to develop in October 2017, Jewish activists began underscoring the importance of “reclaiming the Purim narrative for Queen Vashti and Queen Esther.”32 One headline in a Jewish newspaper declared, “Vashti Was the First #MeToo Survivor.”33 Erica Brown, in an Atlantic article titled “Having an Esther Moment,” noted that the only argument against championing Vashti as a hero is the tragic fact that “she didn’t change court culture; she was its victim.”34

A 2019 novel, Anna Solomon’s The Book of V., goes so far as to reimagine Vashti as Vivian Barr, a Watergate-era woman who refuses her husband’s demand that she perform a humiliating favor, suggesting that the stories of Vashti and contemporary women are deeply intertwined in ways that the reader might not have recognized. As Solomon put it in an op-ed about the book, “If anything was clear during the Purim celebrations of my childhood – and I’ll be honest, between the costumes and groggers and carnival vibe, not much was clear – it was this: No one wanted to be Vashti.” But further exploration led Solomon to recognize that there was another side to the queen. Perhaps she wasn’t a “leprous prostitute” but a woman who “turns out to be virtuous…maybe even good and beautiful and brave.”35

In sum, ever since “coming to America,” Vashti’s status as a feminist and Black hero has been secure, rising in prominence whenever the subjects of slavery and mistreatment of women have risen on the communal agenda. Yet while Vashti’s legacy as feminist icon in wider American culture seems secure, one chapter has yet to be fully written. What will happen in the Modern Orthodox Jewish community, for whom Vashti is not a blank canvas, but one drawn with sharply contrasting images? Will Modern Orthodox Jewish day schools continue portraying Vashti as a villain? Will she be celebrated instead? Or will the complex question of her character simply be sidestepped by rank and-file classroom educators? Time will tell, though I suspect that in many schools, a transformation is already well underway. Either way, one thing is certain: ever since she arrived on these shores in the nineteenth century, the American view of Vashti has never been the same.

1. Esther Rabba, Petiĥta 12.

2. Esther Rabba 1 to Est. 2:1.

3. Megilla 12b.

4. Megilla 12a–b.

5. Ibid.

6. See Leviticus Rabba, Shemini, 12.

7. See my “Vashti: Feminist or Foe?” The Lehrhaus (March 6, 2019), https://thelehrhaus. com/scholarship/vashti-feminist-or-foe/, and for an excellent summary of the rabbinic portrayal of Vashti, see Malka Z. Simkovich, Zev Farber, and David Steinberg, “Ahasuerus and Vashti: The Story Megillat Esther Does Not Tell You,” https://www. thetorah.com/article/ahasuerus-and-vashti-the-story-megillat-esther-does-not-tellyou, March 6, 2017.

8. See, for example, Jo Carruthers, Esther Through the Centuries (Malden, 2008), 7, 12–13.

9. Laurence A. Turner, “Finding Christ in a Godless Text: The Book of Esther and Christian Typology,” in No One Better: Essays in Honour of Dr. Norman H. Young, ed. Kayle B. de Waal and Robert K. McIver (Oxford, 2016).

10. “Of God’s Word: XXIV,” in The Table-Talk of Martin Luther, trans. William Hazlitt (Philadelphia, 1893).

11. Esther Through the Centuries, 13.

12. Louis Bayles Paton, The Book of Esther: International Critical Commentary (Edinburgh, 1908), 97.

13. Bulletin for Biblical Research 8 (1998): 39–54.

14. Susan Zaeske, “Unveiling Esther as Pragmatic Radical Rhetoric,” Philosophy and Rhetoric 33, no. 3 (2000): 206, summarizes the medieval literature: Churchmen found the Esther story useful in their efforts to influence the rhetorical behavior of noblewomen because it provided a model of a pious queen that seemed particularly appropriate for Christian queens. In his ninth century “Expositio in librum Esther,” Hrabanus Maurus urged the empress Judith (second wife of Louis the Pious) to “[a]lways place Esther, a queen like you, before the eyes of your heart, as someone to be imitated in every act of piety and sanctity” (qtd. in Lois L. Honeycutt, “Intercession and the High-Medieval Queen: The Esther Topos,” in Power and the Weak: Studies on Medieval Women, ed. Jennifer Carpenter and Sally-Beth MacLean, [Urbana, 1995], 129). In a letter to the wife of Charles the Bald, Pope John VIII urged her to advocate on behalf of the church in the same way Esther pleaded for the people of Israel. Likewise, a prayer written for the coronation in 876 of Charles the Bald’s daughter Judith praises Esther as so blessed by God as an intercessor that “by means of her prayers” she was able to incline “the savage heart of the king toward mercy and salvation” (ibid.). Indeed, from the ninth century to the twelfth century, concludes Honeycutt, “at least a passing reference to Esther became nearly formulaic in the literature addressed to medieval queens” (ibid., 133).

15. Zaeske, 193–220.

16. For more on Cotton Mather, see Stuart Halpern’s chapter in this volume.

17. Jacob Mason Spencer, “Hawthorne’s Magnalia: Retelling Cotton Mather in the Provincial Tales,” unpublished Harvard University dissertation, 2015.

18. At least those in Google’s extensive database.

19. Shira Wolosky, “Women’s Bibles: Biblical Interpretation in Nineteenth-Century American Women’s Poetry,” Feminist Studies 28, no. 1 (Spring 2002): 202.

20. Harriet Beecher Stowe, Bible Heroines: Narrative Biographies of Prominent Hebrew Women (New York, 1878), 125, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd. rsm3x2&view=1up&seq=10.

21. As Wolosky notes (p. 202), in 1891, suffragette Anna Howard Shaw similarly praised Vashti in an article entitled “God’s Women,” published in The Woman’s Journal (March 7, 1891).

22. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, The Women’s Bible (New York, 1895), 85–86.

23. Ibid., 87. An even more assertive, self-empowered Vashti appears in Ella Wheeler Wilcox’s “The Revolt of Vashti,” composed in 1909. In 1917, Helen Hunt Jackson struck a similar note in her poem “Vashti,” which appeared in Sonnets and Lyrics (Boston, 1887), 16–17.

24. Somerville, 2003. 25. In a Q&A published on his website (http://www.peterhreynolds.com/dot/Dot_ QandA.html), Reynolds explains:

Q: Where did the name of the main character come from? A: Vashti is the name of the main character in The Dot. This was inspired by a young girl who I met at a coffee shop in Dedham Square, Massachusetts. She was selling flowers to raise money for her school. After I bought a carnation, she asked what I was doing. I said, “Painting. Here…you can have this one. I’ll sign it to you – what’s your name?” “Vashti.” I smiled. “Vashti? You’re the very first Vashti I’ve met! Can I use your name in my next book?” Her big brown eyes lit up. “YES!” She disappeared with the drawing I had made for her. I have not seen her since. Perhaps one day she will discover The Dot and make the connection!

26. https://www.pfaw.org/vashti-for-african-american-women-and-girls/.

27. Albert Murray, The Hero and the Blues (New York, 1995), 13–14.

28. Anthony Pinn, Terror and Triumph: The Nature of Black Religion. The 2002 Edward Cadbury Lectures. (Minneapolis, 2003), 173.

29. Ashley Ross, “The Feminist History of the Jewish Holiday of Purim,” Time (March 23, 2016), https://time.com/4269357/queen-vashti-feminist-history/.

30. Alice Laffey, An Introduction to the Old Testament: A Feminist Perspective (Philadelphia, 1988), 216.

31. Cleveland, 2003.

32. Sheila Katz, “Reclaiming the Purim Narrative for Queen Vashti and Queen Esther, JWI, https://www.jwi.org/articles/reclaiming-the-purim-narrativefor-queen-vashti-and-queen-esther.

33. David Charles Pollack, “Vashti Was the First #MeToo Survivor,” Forward, February 26, 2018, https://forward.com/opinion/395071/vashti-was-the-first-metoo-survivor/.

34. Erica Brown, “Having an Esther Moment,” The Atlantic (March 8, 2020), https:// www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/03/esther-sex-and-power/607534/.

35. Anna Solomon, “The Other Queen of Purim,” Tablet Magazine (March 9, 2020), https:// www.tabletmag.com/jewish-life-and-religion/299486/the-other-queen-of-purim.